When the 40-something reader within the kippah at my ebook occasion in Michigan approached the signing desk, I already knew what he was going to say, if not the humiliating specifics. Readers like him all the time inform me these items. He hovered till most individuals had dispersed, after which described his grocery store journey that morning. One other shopper had rammed him with a cart, arduous. Perhaps it had been an accident, besides the patron had shouted, “The kosher bagels are within the subsequent aisle!” He’d thought of saying one thing to the shop supervisor, however to what finish? In addition to, it wasn’t a lot worse than the baseball recreation the day earlier than, when different followers had thrown popcorn at him and his youngsters.

The latest rise in American anti-Semitism is effectively documented. I might fill pages with FBI hate-crime statistics, or with an inventory of violent assaults from the previous six years and even the previous six months, or with the rising gallery of American public figures saying vile issues about Jews. Or I might share tales you in all probability haven’t heard, akin to one a few threatened assault on a Jewish faculty in Ohio in March 2022—the place the would-be perpetrator was the college’s personal safety guard. However none of that will seize the obscure sense of dread one encounters as of late within the Jewish neighborhood, a dread unprecedented in my lifetime.

I printed a ebook in late 2021 about exploitations of Jewish historical past, with the intentionally provocative title Folks Love Useless Jews. The anti-Semitic hate mail arrived on cue. What I didn’t count on was the torrent of personal tales I acquired from American Jews—on-line, in letters, however principally in particular person, in locations the place I’ve spoken throughout America.

These individuals talked about bosses and colleagues who repeatedly ridiculed them with anti-Semitic “jokes,” mates who turned on them after they talked about a son’s bar mitzvah or a visit to Israel, romantic companions who brazenly mocked their traditions, classmates who defaced their dorm rooms and pilloried them on-line, academics and neighbors who parroted conspiratorial lies. I used to be shocked to find out how many individuals have been getting pennies thrown at them in Twenty first-century America, an anti-Semitic taunt that I assumed had died round 1952. These informal tales sickened me of their quantity and their similarity, a catalog of small degradations. At a time when many individuals in different minority teams have change into daring in publicizing the tiniest of slights, these American Jews as an alternative expressed deep disgrace in sharing these tales with me, feeling that that they had no proper to complain. In spite of everything, as lots of them informed me, it wasn’t the Holocaust.

This text was featured in One Story to Learn At present, a publication by which our editors advocate a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday by means of Friday. Join it right here.

However well-meaning individuals in every single place from statehouses to your native center faculty have responded to this surging anti-Semitism by doubling down on Holocaust training. Earlier than 2016, solely seven states required Holocaust training in colleges. Prior to now seven years, 18 extra have handed Holocaust-education mandates. Public figures who make anti-Semitic statements are invited to tour Holocaust museums; colleges reply to anti-Semitic incidents by internet hosting Holocaust audio system and implementing Holocaust lesson plans.

The bedrock assumption that has endured for practically half a century is that studying in regards to the Holocaust inoculates individuals towards anti-Semitism. But it surely doesn’t.

Holocaust training stays important for educating historic information within the face of denial and distortions. But over the previous yr, as I’ve visited Holocaust museums and spoken with educators across the nation, I’ve come to the disturbing conclusion that Holocaust training is incapable of addressing up to date anti-Semitism. Actually, within the complete absence of any training about Jews alive right now, educating in regards to the Holocaust would possibly even be making anti-Semitism worse.

I. The Museum Makers

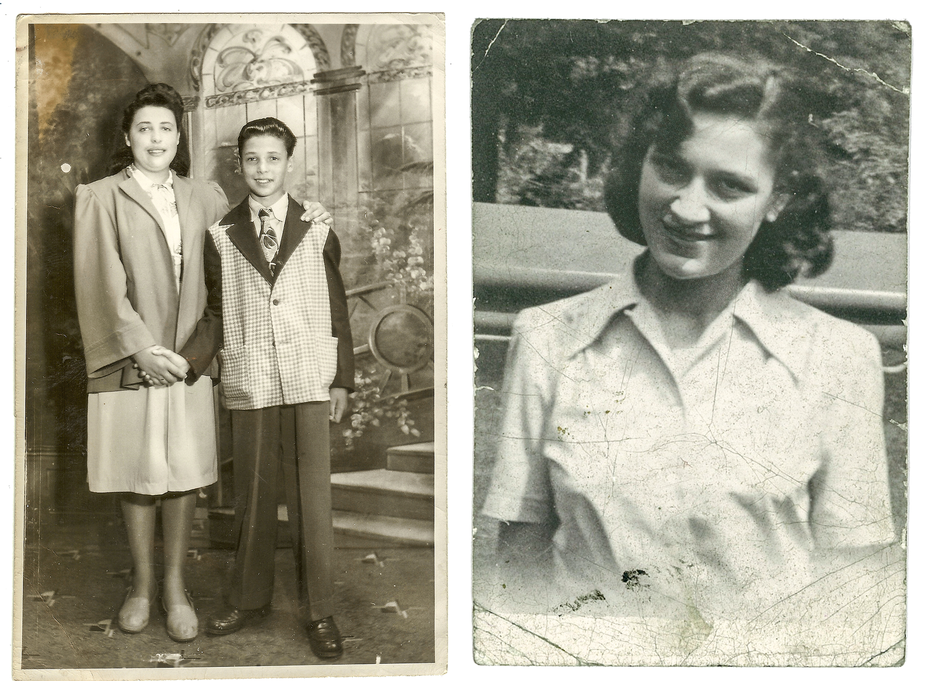

You possibly can divide the story of Skokie, Illinois, “into two durations,” Howard Reich informed me: “Earlier than the tried Nazi march and after.” Reich grew up in Skokie and is a former Chicago Tribune author. His mother and father survived the Holocaust. When Reich was a child within the Chicago suburb within the Nineteen Sixties, they mentioned their experiences solely with different survivors—which again then was typical. “They didn’t need to burden us kids,” Reich defined. “They didn’t need to relive the worst a part of their life.” However the ache was ever current. Skokie’s Jewish neighborhood included a big survivor inhabitants; Reich remembers one neighbor whose recurring nightmares about Nazi canines led him to kick a wall so arduous that he broke his toe.

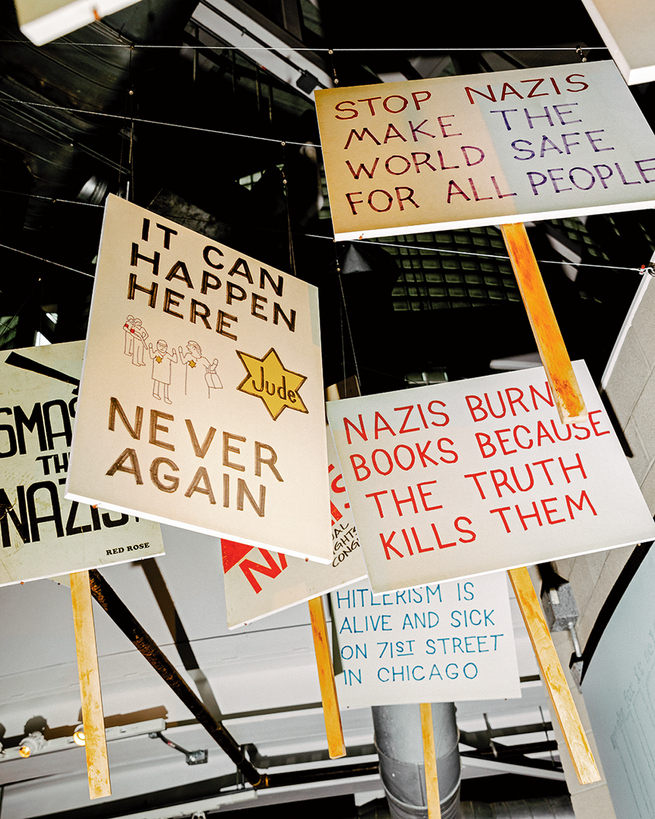

In 1977, the Nationwide Socialist Get together of America needed to march in uniform in Skokie. When the city tried to dam the march, the Nazis, represented by a Jewish ACLU lawyer dedicated to free speech, went to court docket. The case reached the Supreme Court docket; ultimately, the regulation favored the Nazis, though—maybe as a result of they have been sufficiently spooked by the general public backlash—they didn’t march in Skokie in any respect.

The incident impressed many Skokie survivors to talk out about their experiences. They created a Holocaust museum in a small storefront and later efficiently lobbied the state for one among America’s earliest Holocaust-education mandates. If American regulation couldn’t instantly defend individuals from anti-Semitism, they hoped training might.

Final yr, I met Skokie’s mayor, George Van Dusen, and a retired Skokie village supervisor named Al Rigoni in Van Dusen’s workplace. Each males have been concerned in native politics through the Nazi incident.

Like most individuals I spoke with who remembered that point, the lads noticed the result of the threatened march as constructive. “The monks and rabbis—they by no means met and talked to one another till this occurred,” Van Dusen mentioned. “Out of that got here our interfaith council.” Rigoni described how the city created a Human Relations Fee, investing cash in police sensitivity coaching lengthy earlier than that was widespread. At present Skokie holds an annual competition celebrating the 100 or so nationwide origins of its residents. The storefront museum has been changed with the Illinois Holocaust Museum & Schooling Middle, which opened in 2009 as one of many largest Holocaust museums within the nation. The previous storefront is now a mosque. “Solely in Skokie,” Van Dusen mentioned, laughing.

All of it appeared like a contented American story—hatred vanquished, multiculturalism triumphant. However Van Dusen and Rigoni had no solutions for me after I requested why we have been seeing rising anti-Semitism, regardless of many years of Holocaust training. Not lengthy earlier than I visited Skokie, anti-Semitic flyers blaming Jews for the pandemic had been left on individuals’s lawns there and in surrounding cities. The adjoining Chicago neighborhood of West Rogers Park, residence to a big Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, noticed a spree of anti-Semitic assaults in 2022 by which a number of synagogues and kosher companies have been vandalized and a congregant’s automobile window was smashed. Just a few weeks after my go to, a gunman would kill seven individuals and wound dozens extra at a parade within the close by city of Highland Park, which has a big Jewish inhabitants. Though authorities have mentioned there isn’t a indication that the suspect was motivated by racism or spiritual hate, anti-Semitic and racist feedback had reportedly been posted underneath a username believed to be related to him, together with one suggesting that Jews be used as “fireplace retardant” and one other questioning whether or not the Holocaust occurred. The suspect was allegedly thrown out of an area synagogue months earlier than the taking pictures.

“There’s a tremor within the nation. Persons are unsettled,” Van Dusen admitted. He stirred uncomfortably in his seat. “We ask ourselves, ‘Has all of this work that we’ve all completed to coach individuals—has it gotten by means of? If it hasn’t, why?’ ”

The Illinois Holocaust Museum & Schooling Middle is a sufferer of its personal success. After I arrived on a weekday morning to hitch a discipline journey from an area Catholic center faculty, the museum was having a light-weight day, with solely 160 college students visiting (usually, nearer to 400 college students go to the museum each day, alongside others). It was nonetheless so packed that the scholars strained to see the shows. The crowding additionally meant that the majority faculty teams didn’t discover the museum in chronological order; ours was assigned to begin within the gallery describing the liberation of the focus camps, making the historical past arduous to observe.

“Inform me what we name an individual who simply watches one thing happening,” our docent, an area volunteer, prompted.

The scholars have been slouchy and disengaged. However the docent pushed, and somebody lastly answered.

“A bystander,” a boy mentioned.

“What could be the alternative of a bystander?” the docent requested.

The youngsters appeared puzzled. “Activist?” one tried.

“Right here on the museum, we name that particular person an ‘upstander,’ ” the docent mentioned, utilizing a time period that has change into ubiquitous in Holocaust training. “That’s what we’re hoping your era will change into.”

She launched the phrase propaganda, prompting the youngsters to outline it. Within the Thirties, she requested, “was it attainable to observe the information?”

The scholars all shook their head no.

“Okay,” she mentioned with a sigh. “Have you ever ever heard the phrases movie show ?”

With a couple of extra pointed questions, the docent established that the ’30s featured media past city criers, and that one-party management over such media helped unfold propaganda. “If radio’s managed by a sure get together, it’s a must to query that,” she mentioned. “Again then, they didn’t.”

As we wandered by means of the post-liberation galleries, I questioned about that premise. Historians have identified that it doesn’t make sense to imagine that individuals in earlier eras have been merely stupider than we’re, and I doubted that 2020s People might outsmart Thirties Germans in detecting media bias. Propaganda has been used to incite violent anti-Semitism since historic occasions, and solely not often due to one-party management. After the invention of the printing press, a rash of books appeared in Italy and Germany about Jews butchering a Christian youngster named Simon of Trent—an instance of the lie generally known as the blood libel, which might later be repurposed as a key a part of the QAnon conspiracy idea. This craze wasn’t attributable to one-party management over printing presses, however by the lie’s reputation. I used to be beginning to see how isolating the Holocaust from the remainder of Jewish historical past made it arduous for even one of the best educators to add this irrational actuality into seventh-grade brains.

We lastly moved to the museum’s opening gallery, that includes photos of smiling prewar Jews. Right here the docent started by saying, “Let’s set up information. Is Judaism a faith or a nationality?”

My abdomen sank. The query betrayed a basic misunderstanding of Jewish id—Jews predate the ideas of each faith and nationality. Jews are members of a sort of social group that was frequent within the historic Close to East however is unusual within the West right now: a joinable tribal group with a shared historical past, homeland, and tradition, of which a nonuniversalizing faith is however one function. Thousands and thousands of Jews establish as secular, which might be illogical if Judaism have been merely a faith. However each non-Jewish society has tried to pressure Jews into no matter id packing containers it is aware of finest—which is itself a quiet act of domination.

“A faith,” one child answered.

“Faith, proper,” the docent affirmed. (Later, within the gallery about Kristallnacht, she identified how Jews had been persecuted for having the “fallacious faith,” which might have shocked the various Jewish converts to Christianity who wound up murdered. I do know the docent knew this; she later informed me she had abbreviated issues to hustle our group to the museum’s boxcar.)

The docent motioned towards the prewar gallery’s pictures exhibiting Jewish faculty teams and household outings, and requested how the scholars would describe their topics’ lives, primarily based on the photographs.

“Regular,” a lady mentioned.

“Regular, good,” the docent mentioned. “They paid taxes, they fought within the wars—unexpectedly, issues modified.”

Hastily, issues modified. Kelley Szany, the museum’s senior vp of training and exhibitions, had informed me that the museum had made a acutely aware determination to not deal with the lengthy historical past of anti-Semitism that preceded the Holocaust, and made it attainable. To be honest, adequately overlaying this matter would have required a further museum. However the thought of sudden change—referring to not merely the Nazi takeover, however the shift from a welcoming society to an unwelcoming one—was additionally strengthened by survivors in movies across the museum. No marvel: Survivors who had lived lengthy sufficient to inform their tales to up to date audiences have been younger earlier than the struggle, lots of them youthful than the center schoolers in my tour group. They didn’t have a lifetime of reminiscences of anti-Semitic harassment and social isolation previous to the Holocaust. For six-year-olds who noticed their synagogue burn—not like their mother and father and grandparents, who may need survived varied pogroms, or endured pre-Nazi anti-Semitic boycotts and different campaigns that ostracized Jews politically and socially—every thing actually did “all of the sudden” change.

Then there was the phrase regular. Greater than 80 p.c of Jewish Holocaust victims spoke Yiddish, a 1,000-year-old European Jewish language spoken around the globe, with its personal colleges, books, newspapers, theaters, political organizations, promoting, and movie trade. On a continent the place language was tightly tied to territory, this was hardly “regular.” Conventional Jewish practices—which embody extraordinarily detailed guidelines governing meals and clothes and 100 gratitude blessings recited every day—weren’t “regular” both.

The Nazi venture was about murdering Jews, but in addition about erasing Jewish civilization. The museum’s valiant effort to show college students that Jews have been “similar to everybody else,” after Jews have spent 3,000 years intentionally not being like everybody else, felt like one other erasure. Educating kids that one shouldn’t hate Jews, as a result of Jews are “regular,” solely underlines the issue: If somebody doesn’t meet your model of “regular,” then it’s wonderful to hate them. This framing maybe explains why many victims of right now’s American anti-Semitic avenue violence are visibly spiritual Jews—as have been many Holocaust victims.

Like most Holocaust educators I encountered throughout the nation, Szany just isn’t Jewish. And likewise like most Holocaust educators I encountered, she is precisely the form of particular person everybody ought to need educating their kids: clever, intentional, empathetic.

After I requested about worst practices in Holocaust training, Szany had many to share, which turned out to be extensively agreed-upon amongst American Holocaust educators. First on the listing: “simulations.” Apparently some academics have to be informed to not make college students role-play Nazis versus Jews in school, or to not put masking tape on the ground within the precise dimensions of a boxcar with the intention to cram 200 college students into it. Like many educators I spoke with, Szany additionally condemned Holocaust fiction such because the worldwide finest vendor The Boy within the Striped Pajamas, an exceedingly widespread work of ahistorical Christian-savior schlock. She didn’t really feel that Anne Frank’s diary was a sensible choice both, as a result of it’s “not a narrative of the Holocaust”—it presents little details about most Jews’ experiences of persecution, and ends earlier than the writer’s seize and homicide.

Different formally failed strategies embody exhibiting college students grotesque pictures, and prompting self-flattery by asking “What would you have got completed?” One more unhealthy thought is counting objects. This was the self-esteem of a extensively seen 2004 documentary referred to as Paper Clips, by which non-Jewish Tennessee schoolchildren, struggling to understand the magnitude of 6 million murdered Jews, represented these Jews by gathering hundreds of thousands of paper clips. The movie received quite a few awards and an Emmy nomination earlier than anybody observed that it’s demeaning to signify Jewish individuals as workplace provides.

Finest practices, Szany defined, are the alternative: specializing in particular person tales, listening to from survivors and victims in their very own phrases. The Illinois museum tries to “rescue the people from the violence,” Szany mentioned, “to remind folks that this occurred to on a regular basis individuals.” This is the reason survivors have lengthy been a fixture of museum teaching programs. However survivors are getting old. Quickly, none might be left. To deal with this looming actuality, the museum went massive: It despatched survivors to Los Angeles to change into holograms.

Aaron Elster and Fritzie Fritzshall have been among the many Skokie survivors impressed by the Seventies Nazi incident to share their tales; each spoke ceaselessly on the museum. In 2015, on the College of Southern California Shoah Basis, a Holocaust-testimony archive and useful resource heart based by Steven Spielberg, they and a handful of others have been every filmed for 40 hours with the intention to be was holograms. Now, in Skokie, keyword-driven synthetic intelligence permits the holograms to reply to questions from the viewers in a 60-seat theater. As Szany ran a non-public demo of the know-how for me, I requested how guests react to it. “They’re extra comfy with the holograms than the actual survivors,” Szany mentioned. “As a result of they know they received’t be judged.”

We watched a quick movie about Elster’s life in Nazi-occupied Poland: how his household starved in a ghetto from which he finally escaped; how his mom discovered a Catholic girl to shelter his older sister; how that girl initially rejected him, then lastly hid him in her barn’s attic; how he didn’t depart the attic for 2 years. Then Szany summoned the holographic Elster (the actual Elster died in 2018). He spoke from a purple armchair, perky and animated as he answered a softball query she requested about how he’d entertained himself whereas hiding alone: “I used to be in a position to take myself away, to faux. I drew issues in my thoughts. I wrote entire novels in my thoughts.”

I requested him why the girl who took in his sister had hesitated to cover him too.

He appeared startled. “I actually don’t know why Irene wasn’t with me.”

I attempted rephrasing my query, then simplifying it. Elster, with a heat smile, mentioned one thing irrelevant. Quickly I felt as I usually had with precise Holocaust survivors I’d identified after I was youthful: pissed off as they answered questions I hadn’t requested, and vaguely insulted as they handled me like an annoyance to be managed. (I bridged this divide as soon as I realized Yiddish in my 20s, and got here to share with them an unlimited vocabulary of not solely phrases, however individuals, locations, tales, concepts—a mind-set and being that contained not a couple of horrific years however centuries of hard-won vitality and resilience.)

Szany eventually defined to me what the lifeless Elster couldn’t: The girl who sheltered his sister took solely ladies as a result of it was too simple for individuals to verify that the boys have been Jews.

I spotted that I wouldn’t have needed to listen to this reply from Elster. I didn’t need to make this considerate man sit onstage and talk about his personal circumcision with an viewers of non-Jewish youngsters. The concept felt simply as dehumanizing as flattening a boy’s pants to disclose a actuality of embodied Judaism that, each right here and in that barn, had been drained of any that means past persecution. I appeared on the lifeless man smiling in entrance of me and felt a wave of nauseating aid. No less than the actual Elster didn’t must take care of these silly questions anymore.

The holograms weren’t the one elaborate try to seize the previous. In an equally uncomfortable mashup of cool tech and lifeless Jews, the museum presents virtual-reality excursions of Auschwitz, which have additionally been piloted in three colleges. Fritzie Fritzshall, who died in 2021, was my information from past the grave.

In a small room, I placed on a headset. Quickly I used to be exterior Fritzshall’s grandparents’ residence, in Hungary (now Ukraine), after which I used to be in a boxcar sure for Auschwitz, with silhouetted animated figures dropped in round me and a soundtrack of infants screaming as Fritzshall described how her grandfather had died through the suffocating journey.

Right here I’m in a boxcar, I assumed, and tried to make it really feel actual. I spun my head to soak up the immersive scene, which swung round me as if I have been on a rocking ship. I felt dizzy and disoriented, purely bodily emotions that distracted me. Did this not rely as a simulation?

I regained my bearings and joined Fritzshall beside the practice tracks at Auschwitz—Right here I’m at Auschwitz, I assumed—and later adopted her to the outside of the camp’s remaining crematorium, the place she described the final time she noticed her mom, after which into the gasoline chamber. I spun my head round once more. Right here I’m in a gasoline chamber.

I had visited Auschwitz in precise actuality, years in the past. With my headset on, I attempted to summon the emotional depth I remembered feeling then. However I couldn’t, as a result of all the issues that had made it highly effective have been lacking. After I was there, I used to be touching issues, smelling issues, sifting soil between my fingers that the information mentioned contained human bone ash, feeling comforted as I recited the mourner’s prayer, the kaddish, with others, the traditional phrases an undertow of paradox and reward: Could the nice Identify be blessed, eternally and ever and ever. Now I used to be simply watching a film that stretched round to the again of my head. It felt much less like actuality than like a classy online game.

Satirically, this system’s most transferring second was when the VR gave approach to a two-dimensional, animated model of one among Fritzshall’s reminiscences. She was the youngest particular person pressured to do slave labor in a manufacturing facility full of 600 girls. When the opposite girls realized how younger she was, they collected crumbs of their bread ration for her, which she rolled right into a nub no greater than a tooth. They gave her these specks on the situation that, if she survived, she would bear in mind them and share their tales.

The second stayed with me. Solely later did I discover that this system had informed me completely nothing about these different girls. The inventive animation rendered them as black-and-white types with vague faces, a revealing selection. I knew how this faceless crowd had suffered and died. However did that rely as remembering them?

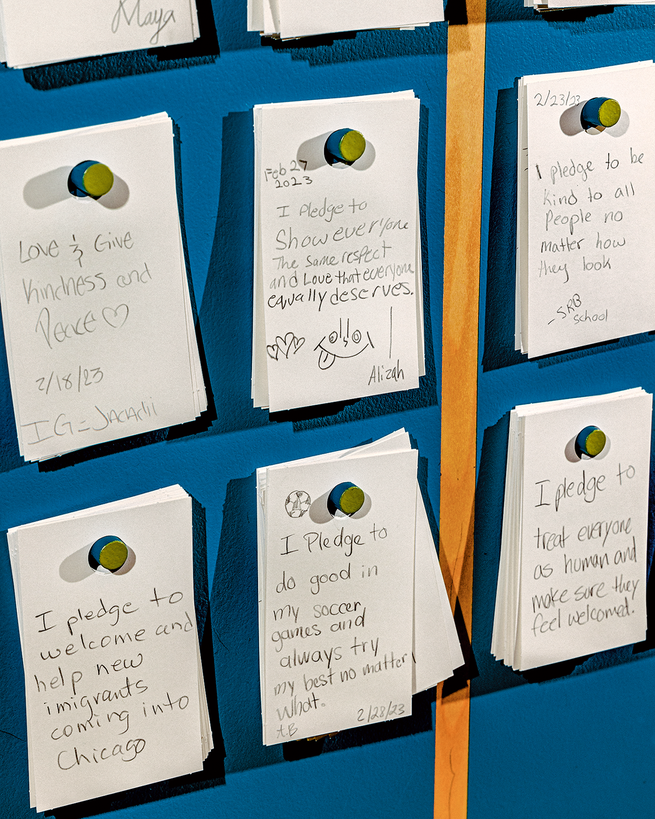

College students on the Skokie museum can go to an space referred to as the Take a Stand Middle, which opens with a shiny show of recent and up to date “upstanders,” together with activists such because the Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai and the athlete Carli Lloyd. Szany had informed me that educators “needed extra sources” to attach “the historical past of the Holocaust to classes of right now.” (I heard this many times elsewhere too.) So far as I might discern, nearly no person on this gallery was Jewish.

Within the language I usually encountered in Holocaust-education sources, individuals who lived by means of the Holocaust have been neatly categorized as “perpetrators,” “victims,” “bystanders,” or “upstanders.” Jewish resisters, although, have been not often categorized as “upstanders.” (Zivia Lubetkin, a Jewish resistance chief who was talked about within the Take a Stand Middle, was a notable exception.) However the post-Holocaust activists featured on this gallery have been practically all individuals who had stood up for their very own group. Solely Jews, the unstated assumption went, weren’t supposed to face up for themselves.

Guests have been requested to “take the pledge” by posting notes on a wall (“I pledge to guard the Earth!” “I pledge to be KIND!”). Screens close to the exit offered me with a menu of “motion plans” to electronic mail myself to assist fulfill my pledge: easy methods to fundraise, easy methods to contact my representatives, easy methods to begin a corporation. It was all so earnest that for the primary time since getting into the museum, I felt one thing like hope. Then I observed it: “Steps for Organizing a Demonstration.” The Nazis in Skokie, like their predecessors, had identified easy methods to manage an indication. They hadn’t been afraid to be unpopular. They’d taken a stand.

I left the museum haunted by the uncomfortable reality that the constructions of a democratic society might probably not forestall, and will even empower, harmful, irrational rage. One thing of that rage haunted me too.

The hassle to rework the Holocaust right into a lesson, coupled with the crucial to “join it to right now,” had at first appeared easy and apparent. In spite of everything, why study these horrible occasions in the event that they aren’t related now? However the extra I thought of it, the much less apparent it appeared. What have been college students being taught to “take a stand” for? How might anybody, particularly younger individuals with little sense of proportion, join the homicide of 6 million Jews to right now with out touchdown in a swamp of Holocaust trivialization, just like the COVID-protocol protesters who’d pinned Jewish stars to their shirt and carried posters of Anne Frank? Regardless of the protesters’ clear anti-Semitism (as a result of, sure, it’s anti-Semitic to make use of the mass homicide of Jews as a prop), weren’t they and others like them doing precisely what Holocaust educators claimed they needed individuals to do?

II. The Curriculum Creators

In Could 2022, I traveled to Seattle to provide a paid lecture on the Holocaust Middle for Humanity about my work on Jewish reminiscence. There I met Paul Regelbrugge, the middle’s director of training; Ilana Cone Kennedy, its chief working officer; and Richard Greene, its museum and know-how director. They eagerly agreed to provide me an inside have a look at their work, it doesn’t matter what I’d say about it.

The Seattle heart is way extra typical of American Holocaust museums than the Skokie one is. Its exhibition is barely greater than a storefront—“the Holocaust in 1,400 sq. toes,” Greene joked—with a show constructed round artifacts from native survivors. The middle primarily focuses on exterior programming, working a audio system’ bureau of native survivors and “legacy audio system” (principally survivors’ kids and grandchildren), inviting visitor lecturers like me, and supplying colleges with “educating trunks” stuffed with classroom supplies. Since 2019, when Washington handed a regulation recommending (although not mandating) Holocaust training, the middle has constructed its personal curriculum and skilled academics throughout the state.

The 2019 regulation was impressed by a altering actuality in Washington and across the nation. Lately, Kennedy mentioned, she’s acquired increasingly messages about anti-Semitic vandalism and harassment in colleges. For instance, she informed me, “somebody calls and says, ‘There’s a swastika drawn within the lavatory.’ ”

Can she repair it? I requested. By educating in regards to the Holocaust? (It appeared to me that the child who drew the swastika had heard in regards to the Holocaust.)

Perhaps not, Kennedy admitted. “What frightens me is that small acts of anti-Semitism have gotten very normalized,” she mentioned. “We’re getting used to it. That retains me up at evening.”

“Sadly, I don’t assume we will repair this,” Regelbrugge mentioned. “However we’re gonna die making an attempt.”

What disturbed me most about this remark was that Kennedy nearly did die making an attempt.

On July 28, 2006, Kennedy, who’s Jewish, was seven months pregnant and in her third yr of working on the Holocaust Middle, which on the time was in an workplace one ground beneath the Jewish Federation of Better Seattle, a nonprofit serving Jewish and neighborhood wants. That day, a person held the 14-year-old niece of a Federation worker at gunpoint and compelled her to buzz him into the constructing. (The Federation’s doorways, like these of most Jewish establishments in America, are perpetually locked for precisely this purpose.) As soon as inside, he ranted about Israel and started taking pictures individuals at their desks. He murdered 58-year-old Pamela Waechter and wounded 5 others. After injuring Dayna Klein, 37 years previous and 4 months pregnant, he held her hostage with a gun to her head as Klein persuaded him to talk with a 911 dispatcher. He finally surrendered. Kennedy had stopped by the Federation’s workplace moments earlier than the assault. After listening to gunshots, she positioned one of many incident’s first 911 calls, and later noticed a lady she’d simply spoken with drenched in blood. Her 911 name made her a witness on the attacker’s trial, at which level she was pregnant along with her second youngster. The irony of experiencing this assault whereas working at a Holocaust-education heart was not misplaced on Kennedy. “There have been Holocaust survivors calling me to see if I was okay!” she mentioned.

Speaking with Kennedy, I spotted, with a jolt of surprising horror, that there was a completely unplanned sample in my Holocaust tour throughout America. Virtually each metropolis the place I spoke with Holocaust-museum educators, whether or not by telephone or in particular person, had additionally been the location of a violent anti-Semitic assault within the years since these museums had opened: a murdered museum guard in Washington, D.C.; a synagogue hostage-taking in a Dallas-area suburb; younger kids shot at a Jewish summer season camp in Los Angeles. I used to be struck by how minimally these assaults have been mentioned within the academic supplies shared by the museums.

The Skokie museum was constructed due to a Nazi march that by no means occurred. However this more moderen, precise anti-Semitic violence, which occurred close to and even inside these museums, not often got here up in my conversations with educators in regards to the Holocaust’s up to date relevance. Actually, apart from Kennedy and Regelbrugge, nobody I spoke with talked about these anti-Semitic assaults in any respect.

The failure to deal with up to date anti-Semitism in most of American Holocaust training is, in a way, by design. In his article “The Origins of Holocaust Schooling in American Public Colleges,” the training historian Thomas D. Fallace recounts the story of the (principally non-Jewish) academics in Massachusetts and New Jersey who created the nation’s first Holocaust curricula, within the ’70s. The purpose was to show morality in a secular society. “Everybody in training, no matter ethnicity, might agree that Nazism was evil and that the Jews have been harmless victims,” Fallace wrote, explaining the subject’s enchantment. “Thus, academics used the Holocaust to activate the ethical reasoning of their college students”—to show them to be good individuals.

The concept Holocaust training can by some means function a stand-in for public ethical training has not left us. And due to its clearly laudable objectives, objecting to it looks like clubbing a child seal. Who wouldn’t need to educate youngsters to be empathetic? And by this logic, shouldn’t Holocaust training, due to its ethical content material alone, routinely inoculate individuals towards anti-Semitism?

Apparently not. “Primarily the ethical classes that the Holocaust is commonly used to show replicate a lot the identical values that have been being taught in colleges earlier than the Holocaust,” the British Holocaust educator Paul Salmons has written. (Germans within the ’30s, in spite of everything, have been aware of the Torah’s commandment, repeated within the Christian Bible, to like their neighbors.) This truth undermines practically every thing Holocaust training is making an attempt to perform, and divulges the roots of its failure.

One drawback with utilizing the Holocaust as a morality play is precisely its enchantment: It flatters everybody. We are able to all congratulate ourselves for not committing mass homicide. This method excuses present anti-Semitism by defining anti-Semitism as genocide prior to now. When anti-Semitism is diminished to the Holocaust, something in need of murdering 6 million Jews—like, say, ramming someone with a purchasing cart, or taunting youngsters in school, or taking pictures up a Jewish nonprofit, or hounding Jews out of total international locations—appears minor by comparability.

However a bigger drawback emerges after we ignore the realities of how anti-Semitism works. If we educate that the Holocaust occurred as a result of individuals weren’t good sufficient—that they failed to understand that people are all the identical, as an illustration, or to construct a simply society—we create the self-congratulatory house the place anti-Semitism grows. One can imagine that people are all the identical whereas being virulently anti-Semitic, as a result of in line with anti-Semites, Jews, with their millennia-old insistence on being completely different from their neighbors, are the impediment to people all being the identical. One can imagine in making a simply society whereas being virulently anti-Semitic, as a result of in line with anti-Semites, Jews, with their imagined energy and privilege, are the impediment to a simply society. To inoculate individuals towards the parable that people must erase their variations with the intention to get alongside, and the associated fable that Jews, as a result of they’ve refused to erase their variations, are supervillains, one must acknowledge that these myths exist. To actually shatter them, one must truly clarify the content material of Jewish id, as an alternative of lazily claiming that Jews are similar to everybody else.

Many Holocaust educators have begun to note this drawback. Jen Goss, who taught high-school historical past for 19 years and is now this system supervisor for Echoes & Reflections, one among a number of main Holocaust-curriculum suppliers, informed me in regards to the “horrible Jew jokes” she’d heard from her personal college students in Virginia. “They don’t essentially know the place they arrive from and even actually why they’re saying them,” Goss mentioned. “Many youngsters perceive to not say the N-word, however they’d say, ‘Don’t be such a Jew.’ ”

“There’s a decline in historical past training on the similar time that there’s an increase in social media,” Gretchen Skidmore, the director of training initiatives at the USA Holocaust Memorial Museum, in Washington, D.C., informed me. “We’ve completed research with our companions at Holocaust facilities that present that college students are coming in with questions on whether or not the Holocaust was an precise occasion. That wasn’t true 20 years in the past.”

Goss believes that one of many causes for the shortage of stigma round anti-Semitic conspiracy theories and jokes is baked into the universal-morality method to Holocaust training. “The Holocaust just isn’t a great way to show about ‘bullying,’ ” Goss informed me, with apparent frustration.

Echoes & Reflections’ lesson plans do deal with newer variations of anti-Semitism, together with the up to date demonization of Israel’s existence—versus criticism of Israeli insurance policies—and its manifestation in aggression towards Jews. Different Holocaust-curriculum suppliers even have materials on up to date anti-Semitism. The Museum of Tolerance, in Los Angeles, whose core exhibition is about Holocaust historical past, not too long ago opened a brand new gallery on this matter. Nonetheless, these suppliers not often clarify or discover who Jews are right now—and their raison d’être stays Holocaust training.

“I labored as an administrator of a faculty Holocaust-resource heart, and I can’t let you know what number of youngsters would are available and be like, ‘I like the Holocaust!’ ” Goss mentioned.

This statement jogged my memory of what I’d heard from different educators. Many academics had informed me that their lecture rooms “come alive” after they educate in regards to the Holocaust. Some had attributed college students’ curiosity to the subject material itself: Its titillating gruesomeness makes college students really feel subtle for tackling a “troublesome” matter, and superior for seeing the evil that their predecessors apparently ignored. However one underappreciated purpose for Holocaust training’s classroom “success” is that after many years of growth, Holocaust-education supplies are simply plain higher than these on most different historic subjects. The entire main Holocaust-education suppliers provide classes that academics can simply adapt for various grade ranges and topic areas. As an alternative of lecturing and memorization, they use participation-based strategies akin to group work, hands-on actions, and “learner pushed” initiatives.

However is there any proof that Holocaust training reduces anti-Semitism, aside from warding off Holocaust denial? A 2019 Pew Analysis Middle survey discovered a correlation between “heat” emotions about Jews and information in regards to the Holocaust—however the respondents who mentioned they knew a Jewish particular person additionally tended to be extra educated in regards to the Holocaust, offering a extra apparent supply for his or her emotions. In 2020, Echoes & Reflections printed a commissioned research of 1,500 faculty college students, evaluating college students who had been uncovered to Holocaust training in highschool with those that hadn’t. The printed abstract exhibits that those that had studied the Holocaust have been extra prone to tolerate various viewpoints, and extra prone to privately help victims of bullying eventualities, which is undoubtedly excellent news. It didn’t, nevertheless, present a big distinction in respondents’ willingness to defend victims publicly, and college students who’d acquired Holocaust training have been much less prone to be civically engaged—in different phrases, to be an “upstander.”

These research puzzled me. As Goss informed me, the Holocaust was not about bullying—so why was the Echoes research measuring that? Extra vital, why have been none of those research analyzing consciousness of anti-Semitism, whether or not previous or current?

One main research addressing this matter was performed in England, the place a nationwide Holocaust-education mandate has been in place for greater than 20 years. In 2016, researchers at College School London’s Centre for Holocaust Schooling printed a survey of greater than 8,000 English secondary-school college students, together with 244 whom they interviewed at size. The research’s most annoying discovering was that even amongst those that studied the Holocaust, there was “a quite common battle amongst many college students to credibly clarify why Jews have been focused” within the Holocaust—that’s, to quote anti-Semitism. When researchers interviewed college students to press this query, “many college students appeared to treat [Jews’] existence as problematic and a key reason behind Nazi victimisation.” In different phrases, college students blamed the Holocaust on the Jews. (This consequence resembles that of a giant 2020 survey of American Millennials and Gen Zers, by which 11 p.c of respondents believed that Jews induced the Holocaust. The state with the very best share of respondents believing this—an eye-popping 19 p.c—was New York, which has mandated Holocaust training for the reason that Nineteen Nineties.)

Worse, within the English research, “a big variety of college students appeared to tacitly settle for a number of the egregious claims as soon as circulated by Nazi propaganda,” as an alternative of recognizing them as anti-Semitic myths. One typical pupil informed researchers, “Is it as a result of like they have been form of wealthy, so possibly they thought that that was form of in a roundabout way evil, like the cash didn’t belong to them[;] it belonged to the Germans and the Jewish individuals had form of taken that away from them?” One other was much more blunt: “The Germans, after they noticed the Jews have been higher off than them, form of, I don’t know, it form of pissed them off a bit.” Hitler’s speeches have been extra eloquent in making related factors.

III. The Academics

The Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum, which opened in 2019, takes up a complete metropolis block within the downtown historic district. I used to be there to attend the annual Sweet Brown Holocaust and Human Rights Educator Convention, the place greater than 60 academics from Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma gathered for professional-development workshops final July. The “upstander” branding I’d encountered in Skokie and elsewhere was much more intense in Dallas. The museum’s foyer featured a large purple wall painted with the phrase UPSTANDER. Every trainer on the convention acquired a tote bag labeled UPSTANDER, a wristband emblazoned with UPSTANDER, and a ebook titled The Upstander.

One of many academics I met was Benjamin Vollmer, a veteran convention participant who has spent years constructing his faculty’s Holocaust-education program. He teaches eighth-grade English in Venus, Texas, a rural neighborhood with 5,700 residents; his faculty is majority Hispanic, and most college students qualify free of charge or reduced-price lunch. After I requested him why he focuses on the Holocaust, his preliminary reply was easy: “It meets the TEKS.”

The TEKS are the Texas Important Data and Expertise, an elaborate listing of state academic necessities that drive standardized testing. However as I spoke extra with Vollmer, it turned obvious that Holocaust training was one thing a lot greater for his college students: a uncommon entry level to a wider world. Venus is about 30 miles from Dallas, however Vollmer’s annual Holocaust-museum discipline journey is the primary time that lots of his college students ever depart their city.

“It’s change into a part of the college tradition,” Vollmer mentioned. “In eighth grade, they stroll in, and the very first thing they ask is, ‘When are we going to be taught in regards to the Holocaust?’ ”

Vollmer just isn’t Jewish—and, as is frequent for Holocaust educators, he has by no means had a Jewish pupil. (Jews are 2.4 p.c of the U.S. grownup inhabitants, in line with a 2020 Pew survey.) Why not deal with one thing extra related to his college students, I requested him, just like the historical past of immigration or the civil-rights motion?

I hadn’t but appreciated that the absence of Jews was exactly the enchantment.

“Some subjects have been so politicized that it’s too arduous to show them,” Vollmer informed me. “Making it extra historic takes away a number of the boundaries to speaking about it.”

Wouldn’t the civil-rights motion, I requested, be simply as historic for his college students?

He paused, considering it by means of. “You must construct a stage of rapport in your class earlier than you have got the belief to discover your personal historical past,” he lastly mentioned.

One other Texas trainer, who wouldn’t share her title, put it extra bluntly. “The Holocaust occurred way back, and we’re not chargeable for it,” she mentioned. “Something occurring in our world right now, the wool comes down over our eyes.” Her colleague attending the convention along with her, a high-school trainer who additionally wouldn’t share her title, had tried to take her principally Hispanic college students to a virtual-reality expertise referred to as Carne y Enviornment, which follows migrants making an attempt to illegally cross the U.S.-Mexico border. Her directors refused, claiming that it might traumatize college students. However they nonetheless be taught in regards to the Holocaust.

Scholar discomfort has been a authorized subject in Texas. The state’s Home Invoice 3979, handed in 2021, is one among many “anti-critical-race-theory” legal guidelines that conservative state legislators have launched since 2020. The invoice forbade academics from inflicting college students “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or some other type of psychological misery on account of the person’s race or intercourse,” and likewise demanded that academics introduce “various and contending views” when educating “controversial” subjects, “with out giving deference to anyone perspective.” (The “discomfort” language was eliminated in later laws; the modified regulation now requires educating “presently controversial” subjects “objectively” and forbids colleges from educating that any pupil “bears duty, blame, or guilt for actions dedicated by different members of the identical race or intercourse.”)

These vaguely worded legal guidelines stand awkwardly beside a 2019 state regulation mandating Holocaust training for Texas college students in any respect grade ranges throughout an annual Holocaust Remembrance Week. In October 2021, a college administrator in Southlake, Texas, made nationwide information after clumsily suggesting that academics would possibly have to current “different views” on the Holocaust. (The district rapidly apologized, however the remarks introduced public consideration to the chilling impact these sorts of payments can have on educating about bigotry of any sort.)

Texas academics are additionally legally required to excuse college students from studying assignments if the scholars’ mother and father object to them. The Dallas museum’s president and CEO, Mary Pat Higgins, informed me that the administrator who’d made the viral remarks in Southlake is a robust proponent of Holocaust training, however was acknowledging a actuality in that college district. Yearly, the administrator had informed Higgins, some mother and father in her district object to their kids studying the Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel’s memoir Evening—as a result of it isn’t their “perception” that the Holocaust occurred.

In a single mannequin lesson on the convention, individuals examined a speech by the Nazi official Heinrich Himmler about the necessity to homicide Jews, alongside a speech by the Hebrew poet and ghetto fighter Abba Kovner encouraging a ghetto rebellion. I solely later realized that this lesson plan fairly elegantly glad the Home invoice’s requirement of offering “contending views.”

The subsequent day, I requested the trainer if that was an unstated purpose of her lesson plan. With seen hesitation, she mentioned that educating in Texas might be like “strolling the tightrope.” This fashion, she added, “you’re basing your views on major texts and never debating with Holocaust deniers.” Lower than an hour later, a senior museum worker pulled me apart to inform me that I wasn’t allowed to interview the employees.

Lots of the visiting educators on the convention declined to speak with me, even anonymously; practically all who did spoke guardedly. The academics I met, most of whom have been white Christian girls, didn’t appear to be of any uniform political bent. However nearly all of them have been pissed off by what directors and oldsters have been demanding of them.

Two native middle-school academics informed me that many mother and father insist on seeing studying lists. Mother and father “wanting to maintain their child in a bubble,” one among them mentioned, has been “the massive stumbling block.” Selecting her phrases rigorously as she described educating the Holocaust, her colleague mentioned, “It’s wholesome to start this research by speaking about anti-Semitism, humanizing the victims, sticking to major sources, and remaining as impartial as attainable.”

I glanced down at my conference-issued wristband. Wasn’t “remaining as impartial as attainable” precisely the alternative of being an upstander?

In making an attempt to stay impartial, some academics appeared to need to hunt down the Holocaust’s shiny aspect—and ask lifeless Jews about it. Within the museum, the academics and I met one other hologram, the Dallas resident Max Glauben, who had died a number of months earlier. We watched a quick introduction about Glauben’s childhood and early adolescence within the Warsaw Ghetto and in quite a few camps. When the lifeless man appeared, one trainer requested, “Was there any pleasure or happiness on this ordeal? Moments of pleasure within the camps?”

Holographic Glauben shifted uncomfortably in his armchair. “Within the Warsaw Ghetto within the early days,” he mentioned, “there was theater, there was performs, dancing exhibits. There have been musicians initially, however as meals turned scarce, many disappeared.” This didn’t reply the trainer’s query about pleasure within the camps.

Later I learn The Upstander, Glauben’s biography—the ebook the museum distributed to convention individuals. (This was one other of the few situations I encountered of somebody Jewish being referred to as an “upstander.”) Glauben’s experiences through the Holocaust included watching Nazis disembowel Jewish prisoners. He noticed one German officer torture Jews by driving over them together with his motorbike. The Upstander additionally mentions a room in a single camp the place Jewish boys have been routinely raped. Glauben’s reminiscence, he informed his biographer, had blocked what occurred to him when a Nazi took him to that room. However after studying many years later about what went on there, he says within the ebook, “I believe he abused me.” These experiences, hardly uncommon for Jewish victims, weren’t the work of a faceless killing machine. As an alternative they reveal a gleeful and imaginative sadism. For perpetrators, this was enjoyable. Asking this lifeless man about “pleasure” appeared like a basic misunderstanding of the Holocaust. There was loads of pleasure, simply on the Nazi aspect.

Within the academic sources I explored, I didn’t encounter any discussions of sadism—the enjoyment derived from humiliating individuals, the dopamine hit from touchdown fun at another person’s expense, the self-righteous excessive from blaming one’s issues on others—despite the fact that this, relatively than the fragility of democracy or the passivity of bystanders, is a significant origin level of all anti-Semitism. To anybody who has spent 10 seconds on-line, that sadism is acquainted, and its supply is acquainted too: the concern of being small, and the need to really feel massive by making others really feel small as an alternative.

The numerous Holocaust academic supplies I’d perused typically offered Nazis as joylessly environment friendly. However it’s extremely inefficient to interrupt mass homicide by, say, forcing Jews to bop bare with Torah scrolls, because the Yiddish poet Avrom Sutzkever testified about on the Nuremberg trials, or forcing Jews to make pornographic movies, because the educator Chaim A. Kaplan documented in his Warsaw Ghetto diary. Nazis have been, amongst different issues, edgelords, in it for the laughs. So, for that matter, have been the remainder of historical past’s anti-Semites, then and now. For People right now, isn’t this probably the most related perception of all?

“Folks say we’ve realized from the Holocaust. No, we didn’t be taught a rattling factor,” Kim Klett informed me one night through the convention, over bright-blue margaritas. Klett is a longtime trainer in Mesa, Arizona, and a facilitator for Echoes & Reflections. An teacher on the Dallas convention, she additionally trains Holocaust educators throughout the U.S.

“Folks glom on to this concept of the upstander,” she mentioned. “Children stroll away with the sense that there have been a whole lot of upstanders, and so they assume, Sure, I can do it too.” The issue with presenting the much less inspiring actuality, she advised, is how mother and father or directors would possibly react. “In the event you educate historic anti-Semitism, it’s a must to educate up to date anti-Semitism. A number of academics are fearful, as a result of should you attempt to join it to right now, mother and father are going to name, or directors are going to name, and say you’re pushing an agenda.”

However weren’t academics purported to “push an agenda” to cease hatred? Wasn’t that all the hope of these survivors who constructed museums and lobbied for mandates and turned themselves into holograms?

I requested Klett why nobody appeared to be educating something about Jewish tradition. If the entire level of Holocaust training is to “humanize” those that have been “dehumanized,” why do most academics introduce college students to Jews solely when Jews are headed for a mass grave? “There’s an actual concern of educating about Judaism,” she confided. “Particularly if the trainer is Jewish.”

I used to be baffled. Academics who taught about industrialized mass homicide have been fearful of educating about … Judaism? Why?

“As a result of the academics are afraid that the mother and father are going to say that they’re pushing their faith on the youngsters.”

However Jews don’t try this, I mentioned. Judaism isn’t a proselytizing faith like Christianity or Islam; Jews don’t imagine that anybody must change into Jewish with the intention to be particular person, or to get pleasure from an afterlife, or to be “saved.” This appeared to be one more fundamental truth of Jewish id that nobody had bothered to show or be taught.

Klett shrugged. “Survivors have informed me, ‘Thanks for educating this. They’ll take heed to you since you’re not Jewish,’ ” she mentioned. “Which is bizarre.”

“Bizarre” is one approach to put it. One other may be “enraging,” or “devastating,” or maybe we could possibly be sincere and simply say “There is no such thing as a level in educating any of this”—as a result of anti-Semitism is so ingrained in our world that even when discussing the murders of 6 million Jews, it might be “pushing an agenda” to inform individuals to not hate them, or to inform anybody what it truly means to be Jewish. Higher to maintain the VR headset on and keep on the monitor. Jews have one job on this story, which is to die.

This made me, within the language of Texas Home Invoice 3979, uncomfortable.

The Dallas Museum was the one one I visited that opened with an evidence of who Jews are. Its exhibition started with temporary movies about Abraham and Moses—limiting Jewish id to a “faith” acquainted to non-Jews, nevertheless it was higher than nothing. The museum additionally debunked the false cost that the Jews—relatively than the Romans—killed Jesus, and defined the Jews’ refusal to transform to different faiths. It even had a panel or two about up to date Dallas Jewish life. Even so, a docent there informed me that one query college students ask is “Are any Jews nonetheless alive right now?”

I couldn’t blame the youngsters for asking. American Holocaust training, on this museum and practically in every single place else, by no means ends with Jews alive right now. As an alternative it ends by segueing to different genocides, or to different minorities’ struggling. (In Dallas, these topics took up most of two museum wings.) This erasure feels fully regular. Higher than regular, even: noble, humane.

However when one reaches the tip of the exhibition on American slavery on the Nationwide Museum of African American Historical past and Tradition, in Washington, D.C., one doesn’t then enter an exhibition highlighting the enslavement of different teams all through world historical past, or a room filled with interactive touchscreens about human trafficking right now, asking that guests change into “upstanders” in combating it. That method could be an insult to Black historical past, ignoring Black individuals’s present experiences whereas turning their previous oppression into nothing however an emblem for one thing else, one thing that really issues. It’s dehumanizing to be handled as an emblem. It’s much more dehumanizing to be handled as a warning.

IV. A Manner Ahead

How ought to we educate kids about anti-Semitism? Listening to Charlotte Decoster, the Dallas museum’s director of training, I glimpsed a attainable path. Decoster started her convention workshop by introducing “vocabulary must-knows.” On the high of her listing: anti-Semitism.

“In the event you don’t clarify the ism,” she cautioned the academics within the room, “you will want to clarify to the youngsters ‘Why the Jews?’ College students are going to see Nazis as aliens who convey with them anti-Semitism after they come to energy in ’33, and so they take it again away on the finish of the Holocaust in 1945.”

She requested the academics, “What’s the primary instance of the persecution of the Jews in historical past?”

The academics checked out her blankly till one raised a hand. “I as soon as learn one thing about Jews getting blamed and killed for the Black Demise,” the trainer mentioned. “That was an enormous eye-opener for me.”

Decoster appeared unimpressed. “Are you able to consider something sooner than that?”

Extra clean stares. Lastly, one girl mentioned, “Are you speaking in regards to the Outdated Testomony?”

“Suppose historic Egypt,” Decoster mentioned. “Does this sound acquainted to any of you?”

“They’re enslaved by the Egyptian pharaoh,” a trainer mentioned.

I wasn’t certain that the biblical Exodus narrative precisely certified as “historical past,” nevertheless it rapidly turned clear that wasn’t Decoster’s level. “Why does the pharaoh choose on the Jews?” she requested. “As a result of that they had one God.”

I used to be shocked. Hardly ever in my journey by means of American Holocaust training did I hear anybody point out a Jewish perception.

“The Jews worship one God, and that’s their ethical construction. Egyptian society has a number of gods whose authority goes to the pharaoh. When issues go fallacious, you may see how Jews as outsiders have been perceived by the pharaoh because the risk.”

This surprising understanding of Jewish perception revealed a profound perception about Judaism: Its rejection of idolatry is equivalent to its rejection of tyranny. I might see how which may make individuals uncomfortable.

Decoster moved on to a snazzy infographic of a wheel divided in thirds, every explaining a part of anti-Semitism: “Racial Antisemitism = False perception that Jews are a race and a risk to different races,” then “Anti-Judaism = Hatred of Jews as a spiritual group,” after which “Anti-Jewish Conspiracy Idea = False perception that Jews need to management and overtake the world.” The third half, the conspiracy idea, was what distinguished anti-Semitism from different bigotries. It allowed closed-minded individuals to congratulate themselves for being open-minded—for “doing their very own analysis,” for “punching up,” for “talking reality to energy,” whereas truly simply spreading lies.

This, she introduced, “aligns with the TEKS.”

The academics wrote down the knowledge.

The subsequent day, the academics listened in silence to J. E. Wolfson of the Texas Holocaust, Genocide, and Antisemitism Advisory Fee as he walked them by means of a historical past of anti-Semitism in excruciating element, sharing medieval propaganda pictures of Jews consuming pig feces and draining blood from Christian kids. Wolfson clarified for his viewers what this centuries-long demonization of Jews truly means, citing the scholar David Patterson, who has written: “In the long run, the antisemite’s declare just isn’t that every one Jews are evil, however relatively that every one evil is Jewish.”

Wolfson informed the academics that it was vital that “anti-Semitism shouldn’t be your college students’ first introduction to Jews and Judaism.” He mentioned this nearly as an apart, simply earlier than presenting the pig-excrement picture. “In the event you’re educating about anti-Semitism earlier than you educate in regards to the content material of Jewish id, you’re doing it fallacious.”

I assumed in regards to the caring, devoted educators within the room, all dedicated to stamping out bigotry, and knew from my conversations with them that this—introducing college students to Judaism by the use of anti-Semitism—was precisely what they have been doing. The identical could possibly be mentioned, I spotted, for practically all of American Holocaust training.

The Holocaust educators I met throughout America have been all obsessive about constructing empathy, a high quality that depends on discovering commonalities between ourselves and others. However I questioned if a more practical approach to deal with anti-Semitism would possibly lie in cultivating a totally completely different high quality, one which occurs to be the important thing to training itself: curiosity. Why use Jews as a way to show folks that we’re all the identical, when the demand that Jews be similar to their neighbors is precisely what embedded the psychological virus of anti-Semitism within the Western thoughts within the first place? Why not as an alternative encourage inquiry in regards to the variety, to borrow a de rigueur phrase, of the human expertise?

Again at residence, I assumed once more in regards to the Holocaust holograms and the Auschwitz VR, and realized what I needed. I desire a VR expertise of the Strashun Library in Vilna, the now-destroyed analysis heart filled with Yiddish writers and historians documenting centuries of Jewish life. I desire a VR of an evening on the Yiddish theater in Warsaw—and a VR of a Yiddish theater in New York. I need holograms of the trendy writers and students who revived the Hebrew language from the lifeless—and I positively need an AI part, so I can ask them how they did it. I desire a VR of the writing of a Torah scroll in 2023, after which of individuals chanting aloud from it by means of the yr, till the yr is out and it’s learn once more—as a result of the ebook by no means modifications, however its readers do. I desire a VR about Jewish literacy: the letters, the languages, the paradoxical tales, the strategies of training, the encouragement of questions. I desire a VR tour of Jerusalem, and one other of Tel Aviv. I need holograms of Hebrew poets and Ladino singers and Israeli artists and American Jewish cooks. I desire a VR for the conclusion of Daf Yomi, the huge worldwide celebration for individuals who research a web page a day of the Talmud and at last end it after seven and a half years. I desire a VR of Sabbath dinners. I desire a VR of bar mitzvah youngsters in synagogues being showered with sweet, and a VR of weddings with flying circles of dancers, and a VR of mourning rituals for Jews who died pure deaths—the washing and guarding of the lifeless, the requisite comforting of the dwelling. I desire a hologram of the late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks telling individuals about what he referred to as “the dignity of distinction.”

I need to mandate this for each pupil on this fractured and siloed America, even when it makes them a lot, way more uncomfortable than seeing piles of lifeless Jews does. There is no such thing as a empathy with out curiosity, no respect with out information, no different approach to be taught what Jews first taught the world: love your neighbor. Till then, we are going to stay trapped in our sealed digital boxcars, following unseen tracks into the longer term.

This text seems within the Could 2023 print version with the headline “Is Holocaust Schooling Making Anti-Semitism Worse?”

While you purchase a ebook utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.